Trigger warning: This article discusses sensitive topics including lynching, police brutality, concentration camps, etc. It also uses images regarding these topics that some people may find disturbing.

In the United States, it seems that many Americans are under the impression we’ve moved past the old days of explicit racist acts, laws, and beliefs.

In American society, it seems that many people are under the impression we’ve moved past the old days of explicit racist acts, laws, and beliefs.

The whitewashing of American history sometimes causes such historical amnesia – but the rememberance of racist crimes such as slavery, the forced relocation of indigenous peoples, and the Chinese Exclusion Acts act as legacies of the implicitly prejudiced and racist foundations our country was built upon.

Some people believe that since we’ve moved on from slavery, the forced relocation of indigenous peoples, and clearly discriminatory laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act, that we’ve turned over a new leaf.

But even today, there are overt acts of racism.

During World War II, the U.S. government forcibly interned more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans into concentration camps. Discriminatory housing laws exclude low-income people (often people of color) from moving into safer neighborhoods. Just these past few years, President Trump has made multiple attempts to change immigration laws to prevent certain nationalities and religions from getting into the country.

But these explicit acts really stem from a deeper, more systemic issue of implicit bias in our country.

So what is this implicit bias, and how does it affect our laws?

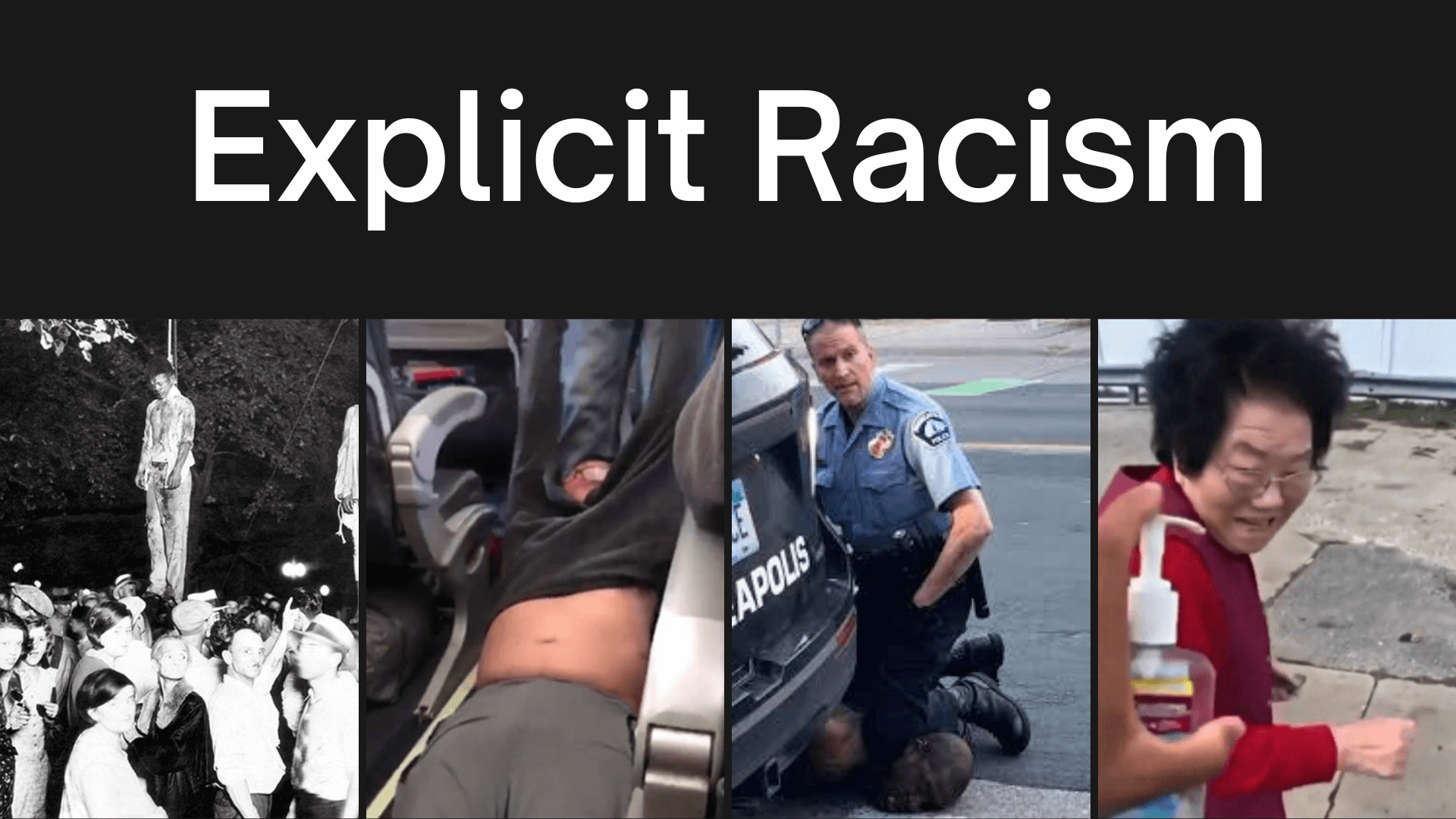

Explicit racism

Explicit and overt acts of racism often happen in public spaces because the perpetrators don’t believe they have done anything wrong. Therefore, they don’t believe they have anything to be ashamed of.

- The lynchings of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion, IN: You’ll see in most of these horrific images of lynching more than one spectator pointing to the victims, as if to make a point that “this will happen to you if you don’t follow our rules and stay in your place.”

- Dr. Dao Duy Anh being dragged off a United Airlines flight: In a modern-day version, the President of United Airlines was quoted as saying that the crew on this flight were following normal procedures by dragging Dr. Dao Duy Anh from the plane after he refused to accept a voucher and change flights.

- The murder of George Floyd: This is of course echoed in the language we hear from law enforcement regarding police brutality and misconduct: that the officers who victimized these citizens were just following normal police procedures.

- Racist coronavirus harassment: However, explicit racism doesn’t always involve life-threatening violence or murder. In March of 2020, this woman was chased down the street with a man threatening to wash her, in reference to President Trump’s racist remarks that China was to blame for the virus.

It’s important to remember that what underlies these explicit forms of racism and policies is a deeper prejudice that’s more difficult to see. That’s why we want to look at the ways implicit biases and prejudices have been institutionalized in laws and methodology our society functions.

Roots of racism

Here’s a helpful video that explains some of the ways this happens.

As the video addresses, it’s important to address these issues systemically because they are systemic problems. However, I also believe it’s important to understand why these types of laws were enacted to begin with, so that we have a better chance going forward to fight racist acts and laws from being institutionalized.

For example, let’s take a look at the infamous ⅗ Clause of the U.S. Constitution: that, for representation purposes in Congress, enslaved Black people would count as ⅗ of a person.

Some scholars argue that this distinction was a “compromise” when the Northern states and Southern states were fighting over representation. But in my opinion, the real issue is so much deeper than that – how could anyone believe they had the right to say that someone was only ⅗ of a human?

Legacy of Racism in the Law

Let’s take a look at some racist policies in the law, historically.

-

Forced relocation of indigenous people in America

It’s easy for us today to think back that this forced relocation was such a long time ago, but the indigenous people were completely uprooted from their homes, taken away from their homeland and traditions. This forced move has an enormous effect even to this day, as Native Americans suffer from terrible rates of poverty, lack of healthcare, and lack of representation.

-

Redlining and gentrification

As the video above explained, redlining was practiced in traditionally mostly Black communities. Now, as these urban areas are being gentrified and reclaimed by better housing developments, many people believe that this is better for the economy. The lower socioeconomic families from these neighborhoods, however, are usually unable to adapt to these newer prices, and so in effect, it’s not very different from redlining.

-

Epidemic of mass incarceration

We’ve all seen the statistics of the U.S. rate of incarceration compared to the rest of the world, as well as the ones that reveal that Black men (and people of color, generally) are so often incarcerated for smaller crimes for longer sentences than their white counterparts. The question is, how can we combat this discrimintation and biases?

-

Electoral College

This is a particularly important subject this year, as we inch closer to Election Day. The fact that the Electoral College does not reflect the popular vote actually goes back to the discussion above of the ⅗ Clause and the struggle between the North and the South. So the anomaly today of the popular vote electing one person but the Electoral College putting another person in office actually can be traced all the way back to these racist roots.

-

The 1980s murder of Vincent Chin in Detroit

A young Chinese-American man at his own bachelor party was beaten to death with a baseball bat by two white men who thought he was Japanese-American. The two men served no jail time. To me, this seems to be a direct result of the implicit biases of the judge in the case – the same way sexual predators are given smaller sentences when a judge believes the victim is somehow “to blame” for their attack.

Implicit racism occurs when we can’t quite pinpoint the racist act. For example, why are more Black people charged with certain crimes than white people? For this question, we need to look at the racial makeup of prosecutors – the ones choosing these charges. For policy, we must examine: what is the racial makeup of people making the laws?

Another example took place at the end of World War II. Japan was already losing the war, and yet the U.S. decided to drop atomic bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima – the only time in history these terrible weapons were ever used. Especially when you look at the racist propaganda cartoons used against the Japanese but not the other Axis powers, many scholars debate the question as to whether the U.S. would have dropped such a weapon on a white, European country such as Germany or Italy.

More recently, President Trump’s threats of a “caravan” of migrants coming to wreak havoc in the U.S. is just another example of the racist rhetoric of “other” people coming to invade. The language is intended to scare and to paint these people as not quite like “us” and therefore, not quite as human.

So how can we fix this?

Thus, internalized implicit racism is manifested in explicit racist acts and policies. Stereotypes about “other types” of people not only lead to policies such as the “Whites Only” signs of the Jim Crow Era, but to privileges of all types.

For another recent example, take a look at these white college students who threw a COVID-19 party to see who would catch the virus first. Because these young people are presumably going to be covered by health insurance if they were to fall sick, they either do not understand or do not care about the repercussions of their actions, and don’t think about the connection of their actions to the death of lower-income people who cannot fall back on health care.

The most important fix moving forward is awareness.

Most recently, George Floyd’s murder raised awareness regarding police brutality.

Only a few years ago, a Washington Post article that examined the enormous number of citizens shot by police over the years and the fractional number of prosecutions seen as a result of these killings. This research prompted the U.S. populous to become more interested in the national progression and exploring the data.

Implicit bias is invisible and insidious, but if we don’t understand where the explicit policies come from, our chances of affecting profound changes and avoiding these issues moving forward, we’ll be playing Whack-a-Mole trying to snuff out these policies.

The real problem has to be addressed on a deeper level, through awareness that sometimes may lead to us feeling uncomfortable with the truth. That’s where the hard work comes, but we need to have the moral courage not just to figure out where these biases come from, but to learn to notice them from the get-go.

[This blog is based on a webinar I did of the same name. Check out the full webinar to hear more discussion of implicit racism and hear my answers to the questions I received during the webinar.]